THIS week’s Mediterranean-style heatwave could be the shape of things to come for Northern Ireland’s climate.

That is the picture emerging from a century’s-worth of data from Northern Ireland’s weather stations.

Taken together, the information reveals a distinctly hotter province than this time last century.

The highest March temperatures ever recorded in the island of Ireland was last Tuesday at Belderrig, Co. Mayo: 22.4 degrees Celsius.

The previous high was 21.3, recorded at Dublin Airport in 1965.

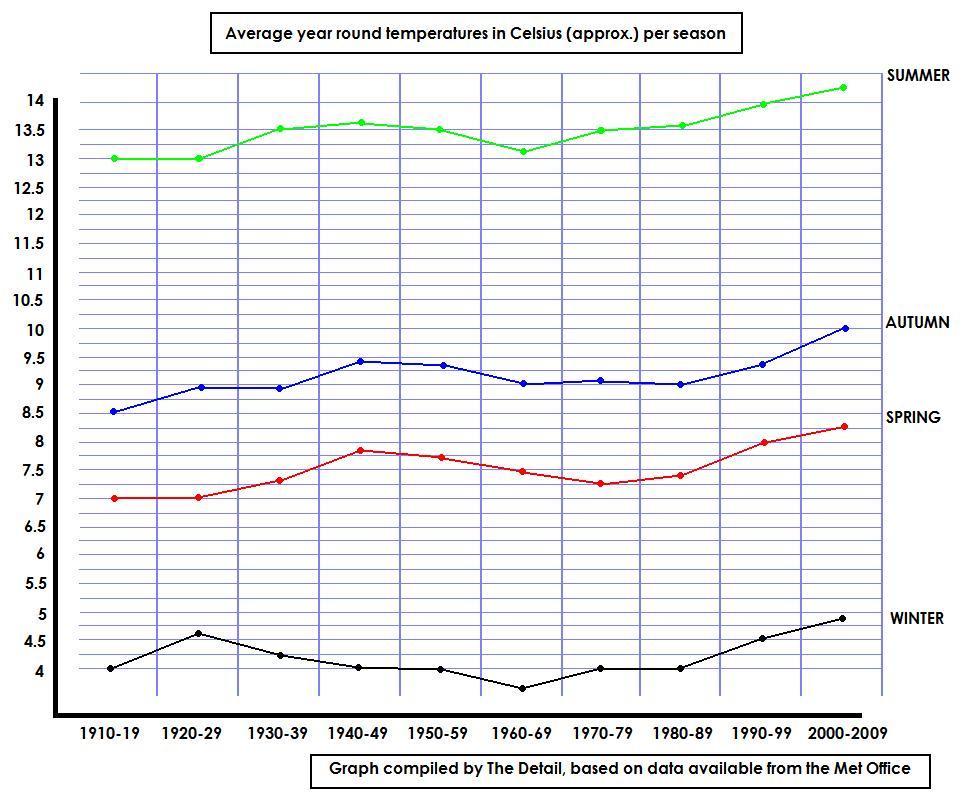

Now The Detail has looked in-depth at the Met Office’s figures for every season dating back to 1910, when records began.

And it seems that last week’s mini-heatwave might not be such a one-off after all – there is a clear trend showing that Northern Ireland is heating up quickly, suggesting more balmy springtimes in the future.

The Met Office’s 35 monitoring stations record temperature data day-and-night for Northern Ireland, which is then combined into an average temperature for each season, for each year.

The Detail took those figures for each decade, combined them, and averaged them out – a process which helps to cancel out anomalies such as a one-off, record-breakingly cold winter, or an especially scorching single summer.

Instead it offers a sober and long-term picture of temperature trends, decade-by-decade.

The result is unmistakable.

Although there was a notable cooling in the middle of the last century, the data shows the temperature has climbed fairly relentlessly ever since, with an especially strong and sustained surge since 1990.

Spring and autumn appear to have been most dramatically affected.

For instance, compared the years 1910 to 1919, Northern Ireland’s springtime (March/April/May) weather over the last decade (2000 to 2009) has been 1.2 degrees Celsius warmer on average.

March itself is 1.6 Celsius warmer, with an average temperature of 6.1 Celcius recorded for the first decade of this millennium, compared to 4.5 Celcius in the 1910s.

But the pattern is similar across all seasons, and combined it shows a rise in average annual temperature of 1.1 Celsius – going from 8.2 Celsius a century ago, to over 9.3 Celcius today.

Although many would welcome a warmer climate, scientists and Friends of the Earth campaigners warn this will be no mere picnic in the park.

Instead such a vast re-jig of the climate could spell problems for agriculture, animals, and ordinary householders.

Outlandish weather phenomena can be expected more often said Gerald Fleming, head of forecasting with Irish weather agency Met Eireann, and RTE weatherman.

He said: “Take a big heatwave event, as happened in France in 2003. If you look backwards in time, you might see it happen two or three times a century.

“If you look forwards, it might be two or three times per decade by the end of this century.

“When you’re looking at long-term changes, you’ve got to look at different indicators; budding times, flowering times.

“There are indications that with spring the first growth and first budding are advancing by one week per decade.

“You look at cherry trees that are in full blossom, where typically they could be in blossom in early May.”

But none of this is straightforward.

He said the expression “global warming” can lead some people to “get the idea that it’s fine because we’ll have more sunny days, but it doesn’t work like that.”

Instead a more erratic climate is likely to be ushered in, making it hard to predict when unseasonal cold snaps or heatwaves will occur.

“By the middle or end of this century, we could be looking at a very different kind of world,” he said.

“We’d expect more (unseasonable heatwaves) in years to come – which isn’t to say we’ll get it next year, or the year after. You have to look at the long term.”

Ray McGrath, head of research at the agency, agrees.

Asked about the last week’s unseasonal warm spell, he said: “It’s not regular. It doesn’t happen that every year we will get a very early spring. There’s a natural variability.

“You could find it would be late. But on the available figures it suggests spring is advancing.

“It’s a big issue. Will it upset ecosystems? No-one really knows for sure. There may be trouble down the road.

“I’d say the likelihood is of more extreme weather; say for example with heavy downpours of rain, and flooding. They’re likely to be a significant issue in the future.

“In terms of warming I don’t think we’d be as badly affected as some areas where they’d get very warm conditions.

“In our part of the world I don’t think people would be too unhappy if you had milder springs and warmer summers. But extreme weather events could be our biggest issue.”

The Met Office in London urged caution though, saying that the recent run of sunny spring “you can’t link directly to climate change”, and it is necessary to look back further than even a century to see the full long-term trends.

Niall Bakewell, activism co-ordinator with lobby group Friends of the Earth, based in Donegall Street Place, said:

“There’s no disagreement amongst climate scientists that the planet is getting hotter, and that it’s almost certainly us causing it to happen.

“There is disagreement on how severe the effects are going to be, but even the most optimistic projections are still devastating for our civilisation.

“Northern Ireland can expect an increase in extreme weather events, including both floods and droughts, and our agriculture will suffer as seasons become unpredictable, and farmers find it harder to know when to sow and reap.”

He called on Stormont’s politicians to join their British counterparts, and enact legally-binding targets for cutting emissions of carbon dioxide by Northern Ireland’s businesses, homes and vehicles.

He added: “All citizens of wealthy industrialised nations must play their part in decarbonising their society, and the first step along this path is to pass climate change legislation with binding targets for reducing emissions.”

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is the main gas blamed for global warming.

Westminster’s Climate Change Act 2008 requires emissions of CO2 to have dropped across the UK in general by 50 per cent by 2027, and 80 per cent by 2050.

If not, the government could be challenged by a judicial review, and faces the embarrassing prospect of being told by a judge that it is breaking its own laws.

The Scottish Assembly has gone further, setting itself even tougher legally-binding targets in 2009 to cut its own emissions by 42 per cent by 2020, and also ultimately ending up with an 80 per cent by 2050.

But there are no legally-binding targets for Wales or Northern Ireland.

The Welsh Assembly in 2010 set itself the non-legally binding target of a three per cent reduction every year.

And Stormont’s Programme for Government has set a target of cutting Northern Ireland’s greenhouse emissions by 35 per cent by 2025, but Friends of the Earth campaigner Declan Allison criticised this for being too vague, and also similarly non-binding.

“There’s no action plan to meet that target,” he said.

“It’s aspiration. The figures are just sort of plucked out of the air. There is no rationale behind it.”

In response to Friends’ of the Earth’s criticisms, the Department for the Environment responded that it does indeed have such a plan.

It said in a statement: “The Programme for Government 2011-15 commits Northern Ireland to continue to work towards a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by at least 35 per cent on 1990 levels by 2025.

“The latest annual projection figure (based on 2009 data) indicates that Northern Ireland emissions in 2025 are likely to reduce by 31 per cent compared with the baseline (1990). The Northern Ireland Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Action Plan published in February 2011 sets out the existing measures that are considered likely to achieve this level of reduction.

“An annual progress report to the Executive will be made available in the coming months.”

Asked what the likelihood of more such freak spring heatwaves is in the future, what impact this is likely to have on ecology and agriculture, and what if any contingency measures are in place to mitigate this, the department said it expected “an increase in winter mean temperature of approximately 1.7 °C” and “an increase in summer mean temperature of approximately 2.2°C” – but it is not clear on what period of time this increase is based.

It also said it expected increases in winter rain, less rain in summer and “sea level rise for Belfast of 14.5cm above the 1990 sea level.”

The Department for Agriculture and Rural Development did not respond to the same questions by close of business on Friday.

But the truth is that even if we act now we may be too late to stop the warming entirely, said Mr McGrath.

“The warming will certainly continue. Even if we sort out greenhouse gases, the warming will continue into the future,” he said.

“The EC have this target they’ve put into policy, to restrict the rise in temperature to no more than two degrees above the pre-industrial era. But that’s the kind of aspiration that would be very hard to hold member states to account on.”