NORTHERN Ireland has seen a dramatic change in policing over the last decade following the formation of the PSNI and the decision of mainstream republicans to endorse support for policing.

But police officers, particularly Catholic recruits, remain in real danger from dissident republicans and are still unable to live in traditionally nationalist areas.

As part of a continuing series of articles investigating the legacy of the Troubles the Detail today looks at the case of one police officer who has never been allowed to return to his home five years after having to flee with his family because of an imminent dissident attack.

And we speak to a retired Catholic police officer, who for more than 30 years was a prime target for republicans, because of his decision to join the RUC. Even at the age of 71, his career choice still impacts on his daily life.

While the threat to PSNI officers remains significant today, there has been strong criticism from the Police Federation that not enough is being done to help officers who have been forced from their homes.

“Since the change to the PSNI hundreds more officers have been forced out of their homes by dissident republicans,” said Police Federation chairman Terry Spence.

“An estimated 64 PSNI officers have had to be re-housed during the last five years as a result of paramilitary threat.”

However Mr Spence says that many officers have discovered that a government scheme, Special Purchase of Evacuated Dwellings (SPED), which was set up to buy the homes of those under threat, will only pay compensation comparable to the current market value of the property, forcing many police officers’ families into severe financial difficulties.

“This means that police officers, who have been forced out of their homes through no fault of their own, are being left with massive mortgages for homes that they can no longer live in, because they will be killed if they ever return.”

In one instance in 2009 the family of a Catholic PSNI officer were forced to flee their home on the southern side of the border after they were warned by police that it was about to be attacked by dissidents.

Since then the policeman’s family have had to live in emergency accommodation and cannot return to their former home.

However because the property is located in the Republic they have been refused permission to have the property purchased under the SPED scheme.

Five years later the family are still living in emergency accommodation with no sign of a resolution in sight.

Mr Spence said that he had repeatedly highlighted concerns to the Police Advisory Board (made up of officials from the Department of Justice, PSNI, Policing Board and Police Federation) to complain about the lack of progress in the case.

“It has been five years since this young officer and his family were forced to flee their home.

“In that time he has received no help at all from the powers-that-be to resolve the crippling financial situation which he and his family have had to endure.

“His children had to leave their schools, his wife has lost her job and still those in authority will do nothing to help them.

“What annoys me is that young Catholics from the Republic of Ireland were deliberately headhunted and encouraged to join the PSNI.

“Now when they are being forced from their homes because of dissident republican or loyalist threats, the state and the PSNI are abandoning them.”

With no sign of a resolution in the case, the Police Federation chairman has criticised the failure to resolve outstanding cases as “morally corrupt”.

“I have asked if young recruits joining the PSNI are told upfront that if they are targeted and have to leave their homes that they will be on their own, because that is what is happening.”

A Policing Board spokeswoman said that it shared concerns regarding the impact on officers who find themselves in negative equity after being forced from their homes.

“Since this issue was first raised, the (Policing) Board has actively engaged with the PSNI and the Department of Justice to try to find an acceptable resolution,” she said.

The spokeswoman said that while the issue was a standing agenda at quarterly meetings of the Police Advisory Board, a resolution had still to be achieved.

“We have been advised however that the strict finance and accounting restrictions placed on public bodies means achieving a solution that satisfies accounting rules in respect of the use of public money and the issue of betterment has unfortunately failed to date.

“The (Policing) Board hopes that a resolution can still be found but the issues are complex and require agreement at government level.”

While the threat level has significantly reduced since the paramilitary ceasefires in 1994, one former police officer says that the danger is unlikely to disappear in the near future.

Throughout the Troubles hundreds of Catholic policemen were forced to leave their homes in nationalist communities because of threats from republican paramilitaries.

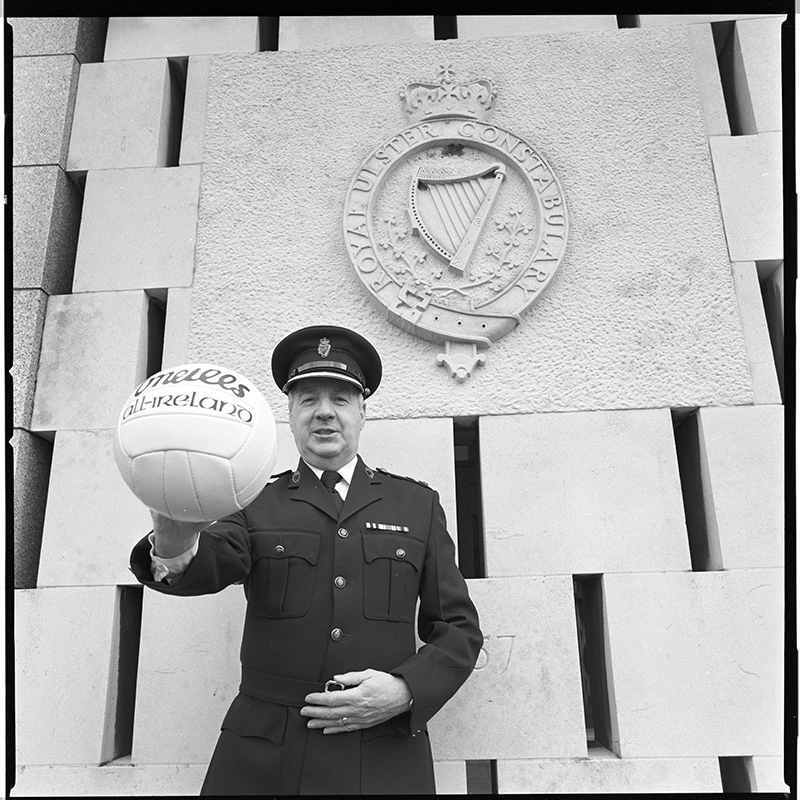

Brian McCargo was a constant target for republican paramilitaries throughout his 34 years as a police officer.

As a young man growing up in Ardoyne in the 1960s he came from a well known nationalist family and was a leading member of his local GAA team.

“Before the outbreak of the Troubles the police were very accepted by the people in Ardoyne. We knew the policemen by name,” he now recalls.

“When you saw a policeman at the top of the street you were on your best behaviour.

“They had a position of authority and you had respect for the police.”

As a schoolboy he remembers how each Sunday local Catholic police officers and servicemen would wear their uniforms to mass at Holy Cross Church.

“No one wanted to kill them, that didn’t happen until later.”

Despite the first warning signs of the Troubles in 1969 and the strong republican beliefs of his mother, Brian McCargo had a deep seated ambition to join the police.

“All my life I wanted to be a police officer, always.”

In 1969 the Hunt Report into the future of policing in Northern Ireland recommended the disbandment of the controversial ‘B’ Specials and greater efforts to encourage more Catholics to join the police, including the establishment of an RUC Reserve.

At 27 years of age and preparing to get married he felt duty bound to join the force.

“I knew there were going to be consequences.

“But the situation was Eddie McAteer (Nationalist MP) and the Catholic Church had accepted the changes recommended in the Hunt Report and I thought it was the right thing to do. You either go down the avenue of violence or, what I felt was the legal, policing path, which was endorsed by the leaders of nationalism.

“Then if there was something wrong, at least people like me would be in there (RUC) to see it and to try to influence it.

“The two saddest days of my life was the day my mother died and the day I was told I couldn’t play Gaelic football for Ardoyne.

“I had joined the (RUC) Reserve and the Belfast Telegraph did an article on my joining. The next week I was picked to play for Ardoyne and I went into the changing room and was told that I had to leave.

“I remember going home and crying my eyes out. Ardoyne (GAA) was my life.

“All of a sudden it was gone.”

Within a short period of weeks the 27 year-old had moved out of his home in Ardoyne never to return.

“Those were the bridges burned. I had to make a very conscious decision – funerals, weddings, birthdays, it was all stopped.”

Over the next three decades he was to witness the deaths of many colleagues whose decision to return home had ended in fatal consequences.

Despite having retired as an Assistant Deputy Chief Constable in 2004, he is still aware that the threat against Catholic officers remains ever present.

“Even today when I go to church I still take a different route. I never go to church with my family. You get into a routine. You think we’re in a new situation, but there’s always a question mark.”

He insists that despite increased support for the police service many Catholic officers still do not feel comfortable enough to live in their own nationalist communities.

“Even if there hadn’t been a dissident threat there was still a ‘No Welcome’ zone (for police). You have to be brutally honest.

“It wouldn’t have matter what you established or how many Catholics joined.

“No Catholics from south Armagh could join the police and continue living in south Armagh. You couldn’t live in the area.

“You could join the police, but many people didn’t want to serve near their home.

“You were creating a greater percentage of Catholics, but not where you wanted them.”

The 71 year-old still yearns for the day when he can return to his native Ardoyne and watch his local GAA team in safety.

“I’ve never forgotten my Ardoyne roots and I’d like to see the day when I can put something back into the area I hailed from and where I have many happy memories.

“Already more people are coming to talk to me and I’m going to talk to them.

“I look forward to going back to the area again.

“I respect people for what they are, irrespective of where they come from, and expect them to take me for what I am.

“I’m Brian McCargo. I was a good, honest, professional police officer.”