Farming is in PJ McMonagle’s blood. He knows no other way of life.

The dairy farmer’s holding at Aughnakeeragh is just seven miles from the border with Strabane in Co Tyrone.

Just south of Raphoe lies the Bronze Age Beltany Stone Circle which could be seen as testament to the fertile region’s long agricultural history – Beltane being the anglicised word for the Gaelic May Day festival when rituals would have been performed to protect the local cattle and celebrate the return of summer.

“I grew up on a farm,” explained PJ. “I took over the farm from my father in 2002. He milked cows before that. Daddy got the farm off his father.

“This is a Land Commission farm that was given to my grandfather who got 14 acres in 1941.”

The Irish Land Commission was responsible for re-distributing farmland in Ireland and PJ’s family eventually grew the 14 acres it was given to the 250 acres he owns today.

Not only has the size of PJ’s farm changed but so has its outlook.

PJ, who chaired the Donegal branch of the Irish Farmers’ Association for four years until 2015, said: “In my grandfather’s time all farms were self-sufficient. They had milk. They had meat because they killed one of the animals. When I was young we would have killed a lamb or a pig. My grandfather had a vegetable garden. Farms years ago were almost self-sufficient. My grandmother made homemade bread and butter.

“That has changed. Farming has changed from a way of life to really focusing on business. A lot of places branched out and went down the road of just dairying or beef or sheep - into one specialised area - where years ago we had a bit of everything. My brother still keeps pigs. I went down the road of dairying and keeping a few sheep. That’s what I liked.”

Today PJ keeps 120 cows for milking, along with 50 sheep and some Connemara ponies, although he only milks just over half of his cattle during the winter.

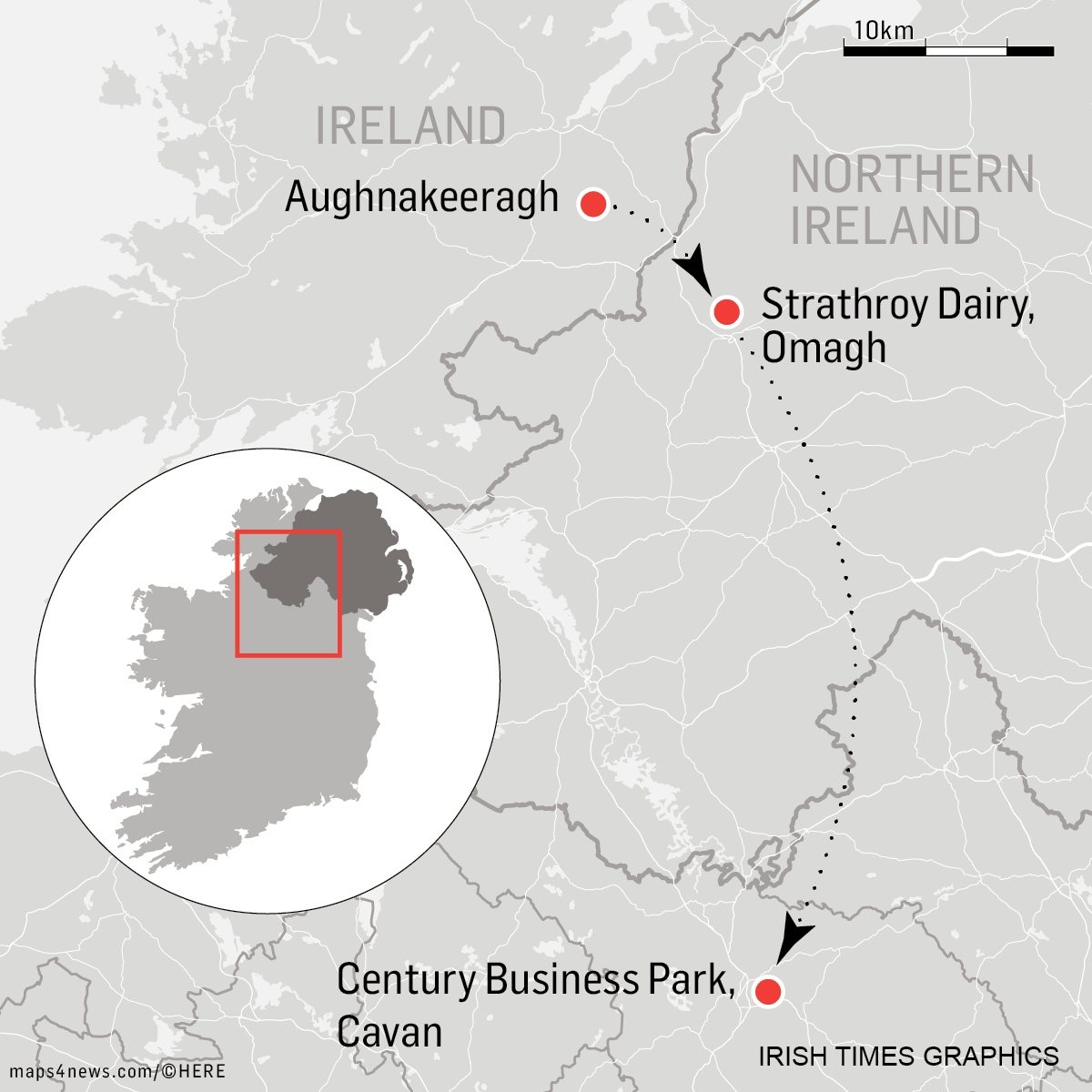

As the debate continues over the UK’s future relationship with the EU, The Detail spent three days following PJ’s milk from the cows on his farm to the processing plant in Northern Ireland and finally to shops in Cavan.

The Detail’s footage, filmed in December 2018, shows how integrated the dairy industry on the island of Ireland is through the journey of milk as it criss-crosses the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

DAY 1 - 6AM: MILKING (Aughnakeeragh, Co Donegal)

A thin crescent moon is still visible in the black early morning sky, nestled amid a blanket of stars, when we enter the milking parlour at around 6am on a frosty Tuesday in December for the first milking of the day.

The 220 by 110 sq ft structure was built in 2009 as a place to keep cattle during the cold winter months and allows dairy farmer PJ McMonagle to milk and house them under the same roof.

The gates to the milking parlour are opened and 25 cows enter at a time, aligning themselves side-by-side along the stalls. As the cattle feed on nuts, PJ attaches automatic pumps to their udders and the milking begins. The animals will return to the parlour at 4pm the same day to be milked again.

Around 500 litres of milk will be taken from 75 cows in any one milking session which means there are approximately 2,000 litres waiting to be collected from PJ’s farm by processor Strathroy Dairy.

There are strict rules around what temperature the milk is allowed to be stored at and it is not permitted to contain any antibiotics.

Andrew Nesson from Strathroy collects milk from PJ's farm in Co Donegal. Picture by Clive Wasson for The Irish Times.

DAY 1 - 2PM: COLLECTION (Aughnakeeragh, Co Donegal)

Strathroy Dairy collects PJ’s milk every other day and it is pumped into a tanker with milk from around half a dozen other farms located in the Republic.

The driver takes a sample from each site he visits and if the milk fails to pass the testing stage at Strathroy’s Omagh headquarters the origin of the contamination can be traced. This rarely happens but could prove costly for the unfortunate farmer whose milk contaminated the tanker as they would be expected to cover the cost of the entire rejected load.

Milk collected over two days is taken from PJ’s farm at around 2pm on Tuesday and it will travel at least 28 miles – longer if the tanker has other farms to visit - before it reaches Strathroy’s processing plant in Omagh. It will cross the border into Northern Ireland around 15 minutes into the journey if PJ’s farm is the last collection point on the driver’s route.

PJ's milk crosses the border from the Republic into Northern Ireland to be processed in Omagh. Picture by Clive Wasson for The Irish Times.

The Republic of Ireland exports 90% of its dairy products to over 130 countries worldwide with the UK accounting for around a quarter of its total dairy exports, according to Bord Bia.

The country exported 93,354 tonnes of milk, worth €24.5m, to Northern Ireland during 2017 while 661,821 tonnes of milk with a value of €221.8m travelled in the opposite direction, according to the Republic’s Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine.

A spokesperson for Stormont’s Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs (DAERA) told The Detail it could not provide information on the volume of milk to cross the border.

However, according to the 2017 Statistical Review of Northern Ireland Agriculture, all of the raw milk produced in Northern Ireland during 2016 was sold to the Republic at a value of £116.7m.

According to the report, which DAERA said is the most recently-published review, this accounted for half of all total external sales and 63% of total export sales from farms in Northern Ireland.

All milk bought by Strathroy is processed in Omagh however milk from the Republic will be kept separate from milk sourced in Northern Ireland.

Strathroy’s commercial director Eamon Lynch explained: “We’ve built a supply base in the Republic because we needed the milk pool and also recognise the importance of supporting farmers across all of Ireland as it is also our marketplace. Over a period of time we’ve very much grown our supply out of the south which is also in line with our sales growth there.

“Quality local produce is important to both retailers and consumers. With Strathroy milk, no matter what part of Ireland they are in, they are assured that their milk is from Irish farms, north or south, and processed to exacting standards in our dairy in Omagh, with depots throughout Ireland helping to guarantee the most efficient delivery service."

DAY 2 - 7AM: PROCESSING (Omagh, Co Tyrone)

The first port of call for Strathroy’s tanker drivers is a small lab to the front of the main building at the Omagh plant where a sample of milk from each load undergoes a number of tests, including checking acidity levels and temperature.

After getting the all-clear from the technicians, who trained at an agricultural college in Loughry, Co Tyrone, the driver can offload the milk he has collected and processing can begin.

Business at Strathroy has finished for the day by the time PJ’s milk arrives shortly after 4pm on Tuesday so it will be stored until the next morning when processing begins again.

It take seconds for plastic containers to be filled with milk at Strathroy Dairy's Omagh processing plant. Picture by Clive Wasson for The Irish Times.

Around 10% of raw milk is cream which is removed and re-added during processing. The amount of cream added to the milk will depend on whether the final product is full fat, semi-skimmed or skimmed milk. Strathroy also sells cream products.

Approximately 85% of the company’s milk is sold in two-litre plastic containers which it makes on site using plastic beads it imports from the Netherlands. It takes seconds to fill a jar with pasteurised liquid milk which then moves quickly along a noisy multi-tiered production line to have a label added by a machine before it is loaded onto trollies that each have the capacity to hold around 80 two-litre containers.

A 40ft lorry awaits beside an adjoining warehouse and typically transfers around 104 trollies – or 8,320 two-litre jars – of milk to a network of distribution depots around Ireland. PJ’s milk is included in a load bound for Cavan.

DAY 2 – 11AM: DISTRIBUTION (Cavan)

The 55-mile journey between Omagh and Strathroy’s distribution centre in Cavan should take around an hour and a half, with PJ’s milk crossing the border back into the Republic just over an hour after it leaves the processing plant.

On arrival, the trollies will be taken into the depot to be stored overnight before the milk is delivered to local retailers on Thursday morning.

DAY 3 – 5AM: DELIVERY (Cavan)

Loading the delivery lorries begins at 4.30am on Thursday with the first shop receiving its supply of milk half an hour later – around 48 hours after it was milked from PJ’s cows.

A lorry with a full load will contain an average of 3,500 two-litre containers of milk and a busy day could see it deliver to up to 50 different shops in the Republic – more than twice the 20 retailers to receive a daily delivery of Strathroy milk from one lorry in Northern Ireland.

“As we operate now there is no border as such so anything that can put a hiccup or hindrance on that is going to impact negatively on how we do our business,” Strathroy’s commercial director Eamon Lynch said. “We are all working under time and efficiency pressures with booking in times etc to meet at depots all over the country. At present, all of that works very smoothly and that is how the business world would want that to stay."

He added: “It’s been very easy because north or south of the border we’ve all been in the same trading block – we’re all part of the European Union. Everything moves freely backwards and forwards. If we lift milk in Strabane or Lifford, it doesn’t matter to us.

“Suddenly [post-Brexit] we might have to be thinking about that in a totally different way because one might be costing us tariffs to bring milk across the border whereas the other is being collected free of duties.

“As we’ve grown our market throughout Ireland over the last 20 to 30 years, we see it all as one place – it’s the island of Ireland. Brexit could potentially put our southern market at risk with substantially increased costs.”

PJ's milk arrives in a shop in the Republic around 48 hours after it is taken from his cows. Picture by Clive Wasson for The Irish Times.

- Camera and editing for 'The journey of milk' film by Ryan Ralph.

- A version of this story also appeared in today's edition of The Irish Times.

By

By