PUPILS in nine Northern Ireland primary schools are taking part in an after school programme which aims to help them achieve basic but important reading and maths skills.

The concept is simple.

The primary one and two children are given three extra hours of literacy work each week and their parents are encouraged to help them with their reading at home.

The schools are all based in disadvantaged areas where, by the age of three, children can currently be as much as one year behind their peers from more affluent areas.

This gap widens beyond the school years with children from disadvantaged backgrounds traditionally being over-represented among those failing to achieve literacy and numeracy skills, qualifications, access to further or higher education and employment.

Poor reading standards have dogged Northern Ireland for decades and have led to the disturbing and long-standing statistic that a quarter of adults in Northern Ireland lack basic literacy and numeracy skills.

The issue of low achievement is often drowned out by news of the extremely high achievement and top GCSE and A-Level grades awarded to pupils at the other end of the ability scale. However, the harsh reality is that many people in Northern Ireland would struggle to read instructions on a medicine bottle or to help their children with their homework.

This week is Adult Learners’ Week (May 12th-18th) which promotes the free literacy, numeracy and ICT training on offer to adults.

Thousands of people have been returning to learning by enrolling on the free essential skills courses offered by the Department for Employment and Learning (DEL) – but at the same time thousands of children are still leaving our schools every year with poor qualifications. And so the cycle of under-achievement continues.

Over 70% of the 168,177 people who enrolled on courses run by DEL between 2002 and 2010 were aged between 16 and 25. This means shortly after leaving the formal education system, many of our teenagers are forced to return to the classroom in a bid to learn basic skills they did not pick up at school. Others never catch up.

Over 8,900 young people (40%) finished Year 12 in 2011 without five or more good GCSEs (grades A*-C), including English and Maths. The new Programme of Government target is to decrease this figure by just 6% to 34% by 2014/15.

POLITICAL HANDLING OF THE ISSUEA report by the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee (PAC) in December 2006 castigated the Department of Education over faltering efforts to improve reading and writing skills among pupils. Not much has improved since then.

The MPs voiced particular concern over the underperformance of Protestant children in deprived parts of Belfast.

The PAC said a strategy on numeracy and literacy launched in 1998 had failed to narrow the “long-standing gap” between the best and lowest achievers, despite the expenditure of £40m. And the committee alleged that a flawed government approach “appears to set up a significant number of children for failure”.

In 2008, the department was criticised after public consultation of its draft new literacy and numeracy strategy was delayed for two months because the document had to be translated into Irish. It was 15 months after the consultation closed in November 2008 before the analysis of responses were released by the department.

The new strategy – ‘Count, Read: Succeed – A strategy for improving outcomes in Literacy & Numeracy’ – was eventually unveiled by former Education Minister Caitriona Ruane in March 2011.

The final report of a taskforce set up to examine poor literacy and numeracy levels in our schools was made public in November 2011 – six months after it was written and handed over to the Department of Education.

The Literacy and Numeracy Taskforce called for stronger action to be taken against consistently underperforming schools, better provision for pupils with special educational needs and an increase in trainee teachers’ entrance requirements. It was also critical of the lack of improvement in many areas since their last report.

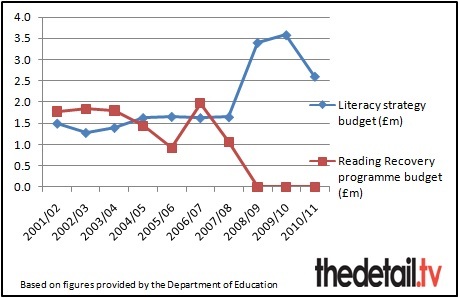

FUNDING FOR READING RECOVERY REDUCED TO ZERORather than increasing investment in improving children’s literacy, the money spent by the Executive on this has decreased dramatically and especially so in the last three years.

In 2010/11 an additional £1m was made available to schools to purchase literacy and numeracy resources.

Apart from this, no further funding has been provided to schools to help them to implement the new ‘Count, read: succeed’ strategy.

A spokeswoman for the department told The Detail: “No additional funding was provided to implement ‘Count, read: succeed’ as schools are expected to raise standards, especially in literacy and numeracy, from within existing funds.”

Funding for a successful reading programme for primary school children struggling with reading has also been axed.

Reading Recovery is a short term, intensive intervention programme used for pupils with the lowest achievement in literacy learning in their first years at school. Children are taught individually by a specially trained teacher and it has a strong record in preventing literacy failure through early intervention.

The programme was first introduced into Northern Ireland in 1994 and in 1998 the department acknowledged its success by setting a target for all schools to have, or have access to, a trained Reading Recovery teacher by 2007.

However, from a peak of almost £2m provided to primary schools by the department for Reading Recovery in the 2006/07 financial year – the financial support plummeted to zero in 2008/09 and this is where it remains.

We requested figures from DENI for funding provided for the department’s literacy strategy and Reading Recovery for the last 10 years. These figures can be seen in the table above.

The Reading Recovery funding was allocated to the education boards for training of teachers in primary schools, the cost of tutors in each of the boards and to provide the programme to small schools on a peripatetic basis.

The DENI spokeswoman said: “The department provided funding to support the Reading Recovery (RR) Programme from 1998/99 to 2007/08.

“Following the completion of the programme, approximately 100 schools who considered RR to be of benefit continued to provide the programme from within their delegated budget, utilising teachers previously trained in RR techniques.

“The education and library boards’ Regional Literacy and Numeracy Action Plans also included provision in 2008/09 (£0.18m) and 2009/10 (£0.16m) to enable each board to retain a tutor to support and sustain RR.”

The department was unable to confirm how many primary schools continue to provide Reading Recovery using their own budget but said it would put this question to the education boards. We are still waiting for a reply.

Targets set by our politicians are pushing for just a few percentage points of change in pupils’ achievement at GCSE level and in key stage testing.

The Programme for Government target relating specifically to literacy levels is surprisingly non-specific. It states that by 2012/13 the Assembly should “develop proposals to significantly improve literacy levels and thereby contribute to addressing multi-generational disadvantage”.

The percentage of pupils achieving the expected level in Key Stage 2 communication in English assessments in their last year of primary school stood at 82% in the 2010/11 school year. This has gone up just over 4% since 2006/07 and still means almost 20% of P7 pupils are failing to get to the level expected of their age group.

The target set for this in ‘Count, read: succeed’ are 86% for 2014/15 and 90%+ as the long-term target.

We asked DENI if it was acceptable for any pupil to leave primary school without basic reading skills.

The department spokeswoman replied: “It is not acceptable for any pupil to leave primary school having underachieved in literacy or numeracy. However, it is important to note that while not every child will achieve at the target level, some of these pupils may still be fulfilling their potential.

“This is why the targets are set at 90%+, rather than 100%. Nevertheless, tackling underachievement remains a priority for the Minister.”

She added that the Education and Skills Authority (ESA) will have a key role to play in ensuring that the objectives in the literacy and numeracy strategy are fully implemented. However, the establishment of ESA is already more than two years behind schedule. It is now due to be up and running by April 2013.

And she added: “Our overarching strategy for raising standards is Every School a Good School, which sets out the belief that schools themselves, through honest self-evaluation informed by data, are best placed to identify and address areas from improvement that can bring about better outcomes for pupils.

“The way teachers are supported to address underachievement is set out in ‘Count, read: succeed’.

“The additional support provided to primary pupils who are underachieving in literacy and numeracy is determined by the class teacher, involving the pupil and their parents where appropriate. The support may take various forms, and is a matter for the professional judgement of the teacher.

“If a pupil continues to underachieve the teacher is expected to get support from: other staff in the school; then if necessary from outside the school.”

Earlier this week (May 15th) Education Minister John O’Dowd announced additional funding for education which included increasing the funding for the Extended Schools programme by £3.6m over the next three years.

“This will assist the involvement of parents in the life of the school and will allow them to support the development of their child’s literacy and numeracy skills,” he claimed in his statement.

However, there were no specific details released on how this would work or how many schools would benefit.

“ACCOUNTABILITY FOR TEACHERS HERE IS WEAK”The Literacy and Numeracy Taskforce – chaired by Sir Robert Salisbury – was set up in 2008 and includes a team of experienced educationalists.

In a comment article written for The Detail, Sir Robert said some key issues still need to be addressed before any sustainable progress in raising standards will be seen.

He writes: “Diagnosis of literacy levels when children first begin school is essential and should be standardised across all establishments so that accurate, reliable comparative data can be established.

“At the moment this process is haphazard and it must be incredibly difficult, especially for teachers in small rural schools to know just how well or how badly they are doing compared with similar schools across the province.”

He also calls for the development of a learning plan for every child to enable early intervention and targeted support to be delivered if required.

Sir Robert argues that accountability for teachers and school leaders is weak in Northern Ireland.

He says: “Under-performing staff should be identified, supported, re-trained or if all else fails, dismissed. Children get one chance in the school system and if they are not receiving the education they deserve then a much tougher approach is clearly necessary.

“Teachers who have little affinity with children, are not reflective, poorly prepared, don’t really know their subject matter or the related pedagogy and lack true ‘passion’ for the job are never going to be effective and should be weeded out.

“The previous four chief inspector’s reports have said that 25% of primary principals and nearly a third of post-primary principals are under-performing. Not tackling this issue has long-term consequences and any uncommitted staff at whatever level must have a detrimental impact on any efforts to improve our standards of literacy.”

He concludes that urgent action is needed: “Getting all young people competent in literacy and numeracy is surely a core purpose of schools and currently the long tail of underachievement shows that far too many pupils are still slipping through the net.

“Without sound literacy skills and adequate qualifications many of our young people will face a very bleak future.”

READY TO LEARNNine primary schools are taking part in Barnardo’s Ready to Learn programme and will be compared with seven schools not receiving the additional support.

The programme is in the second of its three years and will be subject to evaluation by an independent research team from Stranmillis University College and the Institute of Child Care Research.

Ready to Learn is supported by Atlantic Philanthropies and the Office of the First and Deputy First Minister.

Cherith McConnell from Barnardo’s is Literacy Programme Co-Ordinator.

She said: “Ready to Learn aims to raise the standard of literacy achievement in school. We work with the parents in encouraging them to work with their children at home on their literacy and then we also work with the children in school by providing three extra hours a week of literacy in a fun way in an after schools club.

“It has provided a really positive learning environment for the children and we’re really increasing their love of learning and books.

“We are a year and a half into the programme and already we can see improvement in the level of concentration the children have, their ability to listen and to talk and to share knowledge with each other.

“We hope at the end of the three year period that we will have a lot of data to show that giving children more literacy work and encouraging parents can make a huge difference to their love of learning and to their readiness to learn.”

One of the school’s taking part is Cliftonville Integrated Primary in Belfast.

Kathryn Bodles is a P1 and P2 teacher at the school and also literacy co-ordinator.

She said: “A lot of the children come to school with limited literacy skills and Ready to Learn helps to really consolidate and extend what is done in the classroom to help to bridge that gap.

“We have found that it has helped with developing their self-esteem, extending their vocabulary and increasing their confidence.

“The programme has also really helped with our links with parents and they have become more involved in their children’s learning.”

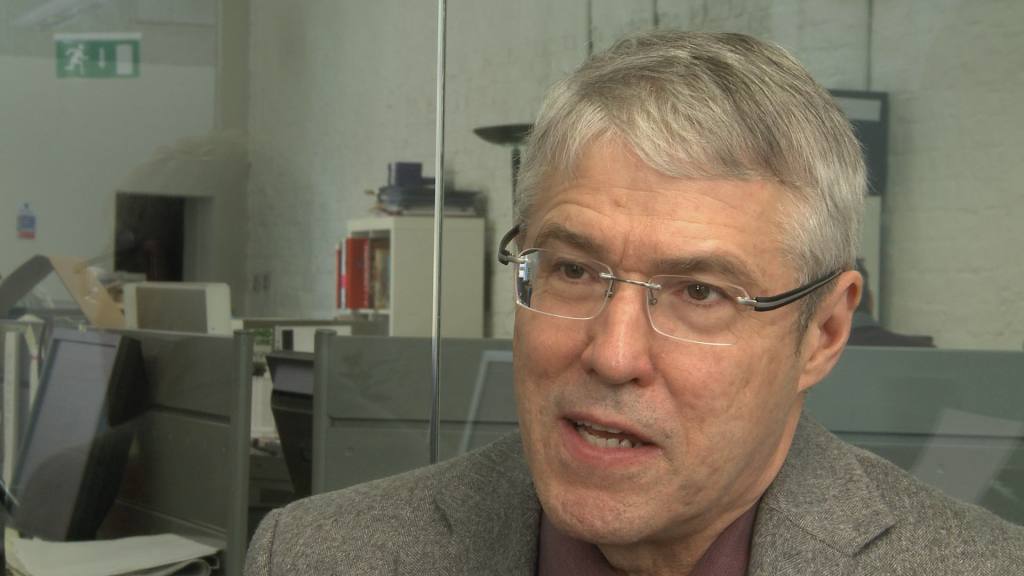

Professor Tim Shanahan is a member of the international advisory committee for Ready to Learn. He is Professor of Urban Education at the University of Illinois in Chicago where he is director of the Center for Literacy.

In an interview with The Detail he said that low literacy levels can impact on issues in communities like unemployment, crime levels and even health problems.

He also said he doesn’t think it is acceptable for children to be leaving school with poor literacy and numeracy.

“If you want children who can leave school, move into the workplace and contribute to society and get a house, start a family and take care of their health care needs, you need them to leave school with literacy levels that are considerably higher than what they are now.”

Prof Shanahan said that Ready to Learn has “exciting possibilities” which could be multiplied through communities.

And he stressed that it is important for parents to let their children know how important their schooling is and that they care about it.

He said: “Many educational problems are intergenerational. Mum or dad didn’t do well at school and didn’t like it. It’s awfully hard for a parent in that situation to encourage their child to be interested in school and to like school.

“Getting parents to show an interest to actually be their child’s first teacher can give the children a real leg up in school and they may do better than perhaps the parents themselves did which is pretty wonderful for a family.”

He said the underachievement of Protestant working class boys in Northern Ireland is “a huge issue”.

“Protestant boys a generation ago would have had a job in the shipyards but now the jobs which used to be done with brawn rather than education have gone away or have been transformed into a different kinds of job.

“I can only imagine that the young men here look and may even say that their educational opportunity went away when the peace came in and when things started to be shared across sectarian lines. There has to be a lot of anger in that.

“But in fact the transformation that is taking place is really taking place across the world. It is a shift away from brawn to brains where you need an education to make a living.”

Prof Shanahan said that Northern Ireland’s Assembly members seem interested in literacy but also appear to be frustrated.

“My sense is that the government knows they have to make moves in this area but I don’t think they’re entirely satisfied that they know what moves to make that will be successful.

“I would try to move their attention away from structural things to the learning experiences of children. Increasing the amount of literacy teaching children get, like Ready to Learn, making sure the curriculum is really complete and ensuring that the quality of lessons is good.”

He concluded by saying that successful literacy programmes should be expanded other schools and especially to children living in deprived areas.

He said: “Education can play a role not just in making people more skilled but also in making them better human beings and better able to work with each other. Given the troubles that Northern Ireland has been through that kind of education is extremely important in an area like this.”

THE HUMAN COSTAs the Department of Education continues to struggle with poor literacy levels, children are continuing to leave school with poor reading and maths skills.

Dermott McCabe, 25, from Enniskillen went back to learning at South West College where he completed courses in literacy and numeracy. He is now studying for a foundation degree in Business Service Management.

Dermott was recently named the Co Fermanagh category winner in DEL’s annual Essential Skills Awards.

He told The Detail: “It’s great to get your learning recognised especially as it was such an effort to get back into learning and I put so much into it.”

Dermott described his time at school as “on and off”.

“There were days that I never wanted to go to school and there were days that I loved getting into school. Some classes I excelled in but I look interest in the classes I didn’t excel in which was English and maths.

“My parents did make the effort to push me but in school it was very difficult for the teacher to push us all individually as we had such a big class.”

Going back to learning has made a big difference to Dermott’s life.

“The difference is being able to stand here and talk to you and have a good conversation as well as with my writing skills. I would have used a lot of text speak whereas now I will actually write proper words because I know how to spell them which is great.

“I also volunteer in the community filling out forms on behalf of a charity so I can now make sure they are accurate and that the spelling and grammar is right in them.”

His goal is now to get to Masters degree level. What is his advice to children who may be struggling at school now?

“I would encourage them to ask for help. Don’t rely on your teacher to come and ask if you are ok. If you don’t get help from your teacher, then ask the principal of the school or even the education board if there’s any additional support they can get.”

Fiona Terrins is a Senior Lecturer for Essential Skills at Southern Regional College with students ranging in age from 16 to 80 and even older.

She warns that low literacy skills have an “extremely detrimental” impact on people’s lives.

“Everything we do in life is to do with whether we can read or write including applying for a job, applying for benefits and living life to the full of one’s capacity.

“It really can be life changing when someone realises that they can achieve and improve their literacy skills through any further education or training organisation.

“It can be a generational thing. You often find people with poor literacy skills have been brought up in a family that have themselves poor literacy skills and it’s a vicious circle. There is a generational problem with literacy prevalent here in Northern Ireland.”

Fiona thinks more should be done in the primary and secondary school sectors when literacy problems arise.

“I’ve always maintained that it is too late for me to target youngsters come into my classrooms at 16. The damage has been done.

“There are real issues when it’s not being picked up at a very basic level when children are five, six, seven, eight.

“They come to me at 16 feeling, and labelled, a failure and it is very hard for us to turn that around and help them feel good and help them realise that they can achieve.”

• For more information on free essential skills classes in literacy, numeracy and ICT in your area visit www.nidirect.gov.uk/knowhow