The Good Friday Agreement was signed 24 years ago this week, relationships north-south and east-west are evolving and changing. In this context, what are the issues that are relevant and to be considered as we think of our future? The Detail is publishing a series of articles which will explore daily cross-border activity on the island of Ireland. The former editor of the Impartial Reporter newspaper, Denzil McDaniel, introduced the series while below, in the second of our stories, Luke Butterly examines how cultural programmes have strengthened cross-border relationships since the Good Friday Agreement.

MUSEUMS reflect a society’s history, but sometimes they are part of it. In 1993, the IRA exploded a 1000lb bomb on the tree-lined Georgian mall at the heart of Armagh City, targeting the local courthouse, and damaging other buildings including the Armagh County Musuem.

“All the windows were blown out at the front, a few at the side. The windows at the front were 16 feet high and covered two floors,” says Catherine McCullough, a museum expert who worked there at the time.

“And we were very lucky that the glass blew out, and not in, because if it was blown in it would have damaged one of the most important collections of George Russell's paintings in the world,” she told The Detail.

The blast damaged windows and the roof, and the museum was closed for a time to clean up: “But didn’t damage any of the collections. And nobody was hurt, that was the main thing,” she said, adding that The Troubles “weren’t easy, for any of us”.

Back then, co-operation with museums in the south was rarely possible. Exhibits crossing the border had to be lifted out of their boxes by hands and examined by Customs officers. The difference between then and now is “like night and day”, McCullough said. “We haven't had to do that for many many many years.”

Today, McCullough is leading a three-year project, commissioned by the Irish Museums Association and Ulster University, that has been looking at how European Union monies have impacted on museums on both sides of the border.

Museums are viewed as the poster child of cross-border co-operation, with a report by Ulster University and the Irish Museums Association (IMA) in 2018 declaring that they could be “viewed as a marker of best practice”.

The EU money encouraged cross-border co-operation: “They've always known each other really well, but there had been few and far between cross border projects,” says McCullough, adding it helped to hire more staff “to do the things they would like to do, and this is a chance to do it”.

One of the leading examples of such co-operation is that between county museums in Cavan and Fermanagh, who have worked together on exhibits to connect “people, places and heritage” since 2004, backed to the tune of €1.5m.

Both museums used exhibitions and engagement events to tackle issues around prejudice and sectarianism; creating a series of cross-community, cross-border partnerships among schools and adult groups that resulted in heritage trails, travelling exhibitions, oral history archives, and workshops.

“It has led to a very strong body of work, as well as knowing that thousands of kids, and hundreds of adults, went through these peace programmes.”

Last year, the Dublin and Belfast administrations welcomed a €1billion EU programme to continue Brussels’ funding peace, reconciliation and economic and social development in Northern Ireland and in the Republic’s six border counties.

“The PEACE funding from 1995 onwards gave museums much more of an incentive or push to work together. They've always known each other really well, but there had been few and far between cross border projects,” says McCullough, who has worked in museums since the early 1980s.

Playfully provocative

One such project, “Making The Future”, which ran for three years until the end of last year, explored The Troubles, cultural identity, centenaries, and partition – “the building blocks of cultural identity and how we’ve got to where we are today”, project lead Niall Kerr told The Detail.

“It’s about using collections and using archives that speak to some of those things, and then giving people a space where they can be creative, and have a voice and have a say around what they would like to talk about.”

Funded to the tune of €1.8m, Making The Future held 130 events on both sides of the border, such as film screenings and lectures, including asking people to create a portrait that they felt was important to them, ranging from mixed marriages or growing up after The Troubles.

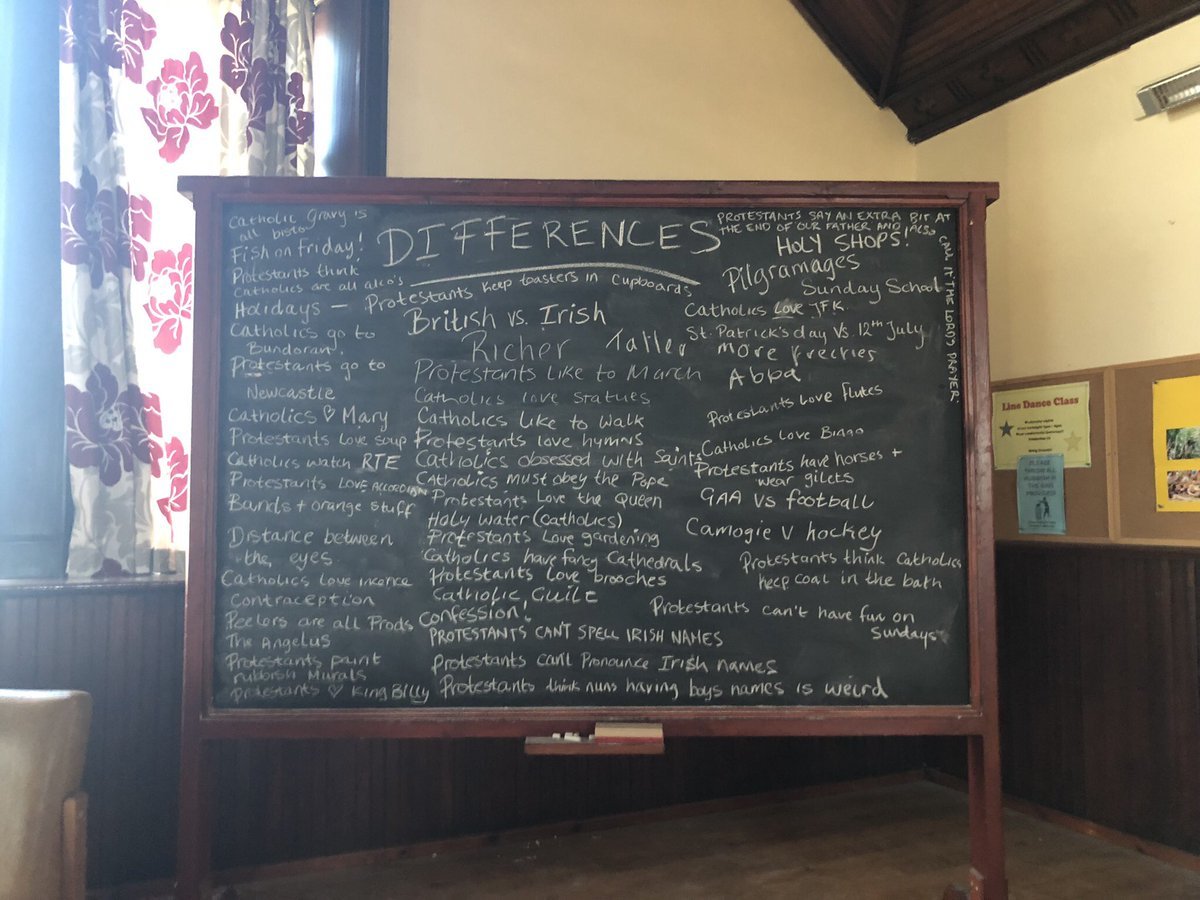

Meanwhile, museums have sought to use popular culture to engage with young people, including copying the famous “Derry Girls” episode where students answered a blackboard test to discover whether they are Catholic or Protestant.

“We use that as a kind of hook, as a starting off point, for people to be what we call ‘playfully provocative’ with issues of cultural identity. We try to tease out how cultural identity has been formed over the last couple hundred years,” Kerr goes on.

The museums are quietly bringing about change with the students: “They've got a better understanding of the history of Ireland and Northern Ireland from the last 100 years; that they're less sectarian, less prejudiced, and less racist.

“We find that this is a really unique programme model for dealing with issues of the past. And using heritage, using collections, using archives and using digital and creative approaches is providing opportunities for people to open up where they haven't before,” he went on.

Natural alignment

The advent of EU peace funding also contributed to a boom in the number of museums. Around a quarter of the museums asked in the last all-island survey from 2016 said they were founded in those decades.

There are approximately 230 museums across the island of Ireland, at least one in each county. Many are volunteer and community-led: the overwhelming majority are staffed by fewer than 10 paid employees, and many operate on small budgets and say they are ‘very dependant’ on volunteers. Yet together, those museums welcomed more than six million visitors in a single year, a third of which were from overseas. The figures are likely to be far from the full picture, as many Irish museums do not consistently record visitor figures.

The purpose of museums has changed radically since the 1990s. Instead of being seen as repositories of collections they are today seen as space to encourage dialogue, inclusion and community engagement across boundaries.

“Most of the programming within museums is towards community building,” the Irish Museums’ Association director, Gina O’Kelly told The Detail, “The ultimate goal is that representation of the different voices in the museums.

Having those insights from the different communities that are working with you is invaluable. You're seeing a huge amount of that now, which is very welcome because it is adding a whole new layer of voices into the museum.”

The impact of museums in promoting peace and reconciliation has been recognised by both governments. The North’s Department of Communities has previously praised the work of museums in creating “a shared and better future”, noting that they “can be catalysts for bringing communities together both physically and through formal and informal opportunities to explore the complexities of history and culture".

The Republic’s Department for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, which annually funds a range of cross-border projects separately from EU peace funding, has said that culture “operates beyond borders and boundaries and can facilitate cross-community and cross-cultural understanding at the deepest level".

Founded in the 1970s, the IMA was a cross-border body ahead of its time. In Britain, said the IMA’s Gina O’Kelly, museums across England, Scotland and Wales are “quite separate”, but “Northern Ireland is quite aligned with the Republic of Ireland”.

However, Brexit is not helping, says Catherine McCullough: “It's all changing. And that’s going to become more difficult, for anyone trying to get exhibitions in and out of Northern Ireland. Museums and their collections were not at heart of Brexit negotiations,” she goes on.

Equally, the long-term future of European Union funding for Northern Ireland’s museums remains uncertain, but the relationships and ties built up between museums over the last few decades will not go away.

“They would work quite closely together in very informal ways, an almost natural part of the way they work,” Gina O’Kelly goes on, “Those relationships are there anyway, irrespective of whether they are government-funded or not.”

- Luke Butterly is a freelance journalist in Belfast.