By Niall McCracken

THE head of the Northern Ireland Prison Service has said it is moving away from a “one size fits all security regime” and is more reflective of post conflict society in Northern Ireland.

In an extensive interview with The Detail as part of The Legacy series, Director General Sue McAllister, acknowledged that many challenges remained but said huge progress was being made in reforming policies shaped during the Troubles.

However one of Northern Ireland’s most senior academic experts in this area believes the system is still primarily geared towards politically affiliated prisoners.

Queen’s University Criminologist Phil Scraton said issues that are a direct legacy of the Troubles are still present in prisons today.

“The lack of contact and recreation, poor mental healthcare, long periods of lock up, strip searching; there are a catalogue of issues that are a direct legacy of imprisonment during the conflict," he said.

“What that does is undermine the rights of prisoners that would be expected in any other jurisdiction, but are denied here.“

However Sue McAllister claimed huge progress has been made as part of the prison reform programme. In recent years the Northern Ireland Prison Service (NIPS) voluntary redundancy package has allowed over 500 staff to leave the service and it has recruited approximately 300 new staff.

She said: “Of course it’s important that we keep our prisons well ordered and safe but that’s not enough anymore. Now we require our staff to support prisoner rehabilitation. There is much more focus on positive engagement, on role-modelling, on supporting people to change.”

The Detail can also reveal that routine strip searching has been stopped in Northern Ireland’s women’s prison, while a controversial unit re-integrating offenders into society is set to reopen in north Belfast.

Also as part of our investigation today The Detail can reveal that more than fifteen years after the Good Friday Agreement, Catholics continue to form a higher proportion of the prison population and are more likely to be punished when behind bars. To read this story click here.

AN ETHOS SHAPED BY THE TROUBLESAcademic studies have estimated that 15,000 republicans and between 5,000 and 10,000 loyalists were imprisoned during the conflict.

The Crumlin Road Gaol in north Belfast closed its doors as a prison for the last time in 1996.

In 2000 the high security Maze prison closed, as under the terms of the 1998 Good Friday Agreement 428 inmates were granted early release.

Today there are now four prisons in Northern Ireland, spread over three sites with approximately 1800 prisoners:

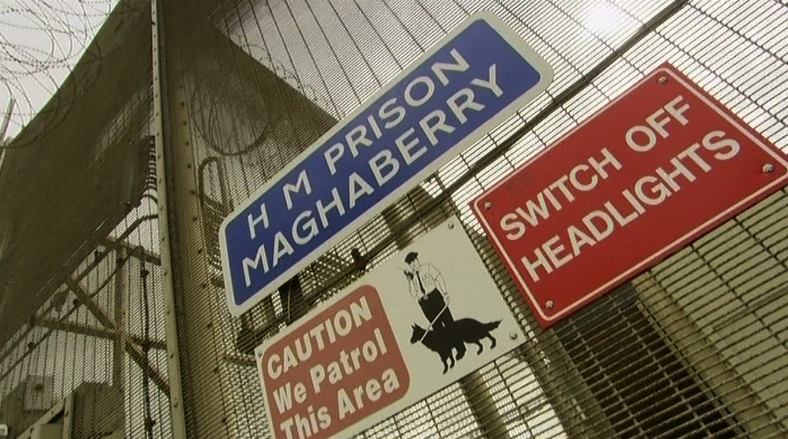

Maghaberry Prison- A high security prison in Co Antrim , housing adult male long-term sentenced and remand prisoners in both separated and integrated conditions.

Magilligan Prison- A medium security prison in Limavady, housing shorter-term adult male prisoners.

Hydebank Wood Young Offenders Centre and Prison- A medium to low security establishment in Belfast accommodating remand and sentenced young offenders between the ages of 16 and 21. It also accommodates female remand and sentenced prisoners in Ash House, a block within the complex.

The prison service during the Troubles was characterised by crises such as the republican hunger strikes in the Maze’s H-Blocks, as well as the constant threat to the lives of prison officers.

Prison protests have continued at a lower level, but so too has the danger posed to prison staff.

As recently as November 2012, David Black became the first prison officer to be murdered in Northern Ireland by paramilitaries in more than 20 years.

He was gunned down by dissident republicans on the M1 motorway as he made his way to work in Maghaberry prison.

He became the 30th prison officer killed since 1974.

In May 2012, just a number of months before Mr Black’s murder, Sue McAllister was appointed as Director General of the Northern Ireland Prison Service and became the first woman to hold the top post in a prison service anywhere in the UK.

Ms McAllister’s time in office coincides with the implementation of a once in a generation review of the entire prison service.

The Prison Review Team’s report was published in October 2011 and outlined 40 recommendations for fundamental reform and identified “a security-led staff culture that derives from the Troubles”.

Ms McAlliser said the findings are the prison service’s strategic blue print for its future.

“The review is essentially the plan of how to reform our prisons to reflect a society that has now seen the Good Friday Agreement and has seen us move to a more normalised position. That process has already started in a number of ways.

“For example, we now train our prison officers differently. Their role has changed so much in 30 years. Of course it’s important that we keep our prisons well ordered and safe but that’s not enough anymore.

“Now we require our staff to support prisoner rehabilitation. There is much more focus on positive engagement, on role-modelling, on supporting people to change.”

In recent years the Northern Ireland Prison Service (NIPS) voluntary redundancy package has allowed 500 staff to leave the service and it has recruited approximately 300 new staff.

“THE MOST COMPLEX PRISON IMAGINABLE”However, Queen’s University professor Phil Scraton said legacy issues stemming from the Troubles can still be found in Maghaberry prison on a daily basis.

In 2003 the UK Government accepted the Steele Review recommendation that republican and loyalist prisoners with paramilitary affiliations should be accommodated separately from each other and from the rest of the prisoner population on a voluntary basis within Maghaberry Prison.

At the moment there are two houses known as “Roe” and “Bush” on the grounds of the County Antrim jail that accommodate separated republican and loyalist prisoners

In May 2011 dissident republicans in Maghaberry prison began a “dirty protest” in their prison wing over the number of forced strip-searches taking place.

The tactic was used by IRA prisoners in the late 1970s and early 1980s. They refused to wash, grew long beards and smeared excrement on the walls of their cells.

While the most recent republican dirty protest ended in November 2012, a previous story by The Detail revealed that dirty protests were still taking place at Maghaberry Prison as recently as August last year by non republican prisoners.

Professor Scraton said Maghaberry creates a prison environment that is entirely unique to Northern Ireland.

“This situation brings about a complex set of interactions between those prisoners and prison staff and it is almost an island within the prison itself. In that sense there is a legacy of the conflict directly in those houses being lived out every day of the week.

“Meanwhile in the rest of the prison, there is the most complex system imaginable. You have remand, pre-sentence, short-term, lifers, with all the complexities that each of these categories bring into prison.

“I don’t think you can ever resolve each of these complexities in one place, with a one size fits all prison officer, with a one size fits all medical service.”

Sue McAllister acknowledged that Maghaberry’s separated units present challenges, but she said it is something they successfully manage.

“It is a tricky business running Maghaberry and it does require us to think slightly differently about how we manage security. For example the political prisoners are kept in what you might call special units and any prison officers working here have additional training.

“So it does require a very flexible approach, it requires a resilience that might be different, we might ask for a different attributes and strengths and skills from those staff, but we support them to work in those areas because they can be particularly challenging.”

A key recommendation of the prison reform programme is that Maghaberry prison is reconfigured into three parts with varying levels of security.

Ms McAllister said that while this was still a work in progress it remained a high priority.

“We have been criticised in the past for having a one size fits all approach to security, but the review programme has established that it’s not necessary, it’s too expensive, it’s too restrictive, and it’s too inflexible.

“When the new system gets under way, it gets us away from thinking that we have to have a single solution for everybody who happens to be in Maghaberry. We can have a high security facility, we can have a facility for sentenced prisoners, and we can have different arrangements for those prisoners who are not yet convicted or sentenced.”

The last inspection report into Maghaberry prison in December 2012 found that safety for prisoners was better than it was three years previous, but that many issues still remained.

The Criminal Justice Inspectorate found that there was still too much bullying and intimidation between prisoners and that in some cases prisoners were spending up to 20 hours in their cells as there was not enough work for them.

Professor Scraton said a lot of the issues can be traced to the legacy of the Troubles in the prison service.

“The lack of contact, the lack of mental healthcare, the lack of recreation; this catalogue of issues undermine the rights of prisoners that would be expected in any other jurisdiction. But they are denied here, that is a direct legacy of imprisonment during the conflict.

“These issues come together to make imprisonment in Northern Ireland over the last decade and right up to the present day, an experience that is not only unjust but actually flagrantly breaches prisoners human rights.”

By

By