How will Brexit affect Northern Ireland's divided society? The Detail mapped data here to show the degree to which Catholic and Protestant communities still live apart. Now, a further article published in partnership with The Irish Times, examines the label 'Northern Irish', finding it is not the new centre ground that many thought.

“Miracles have been happening in Northern Ireland and we have a new vision for Northern Ireland where people will put aside violence, where they will come together to build together one community out of our now divided community, where they will begin to see themselves not as Southern Irish people and not as British people, but as Northern Irish people with a complete new identity.”

(MacNeil, 1976)

AS WITH much of the present day discussion on the Northern Irish national identity, its first mention by the Peace People in 1976 shows enthusiastic optimism, unfettered by the restrictions of evidence. The Northern Irish identity was barely mentioned again for another decade until some surveys began collecting data on its popularity, replacing ‘Anglo-Irish’ which had been used in previous studies.

When the results of the 2011 census (the first to contain this identity option) were published, the fact that almost one half of the population felt at least partially Northern Irish received considerable media attention.

As the societal division here is often (and arguably increasingly) described as an ‘identity conflict’ this was taken by many as an indication of a deep psychological change within the region that could signal a movement towards a natural post-conflict identity, associated with a young, enlightened urban middle class that were keen to emphasise that ‘we are all the same’. This movement was called the ‘Rise of the Northern Irish’ in the Belfast Telegraph (2012).

The aim of this article is not to diminish the genuine pride a considerable section of society here feels towards the strange and beautiful place in which we live. Rather it aims to critically interrogate some of the common claims that are made about this new identity with empirically derived evidence in an effort to raise the debate above assumptions and stereotypes. This article is then primarily a myth busting exercise, where popular narratives are tested with the best data available.

New national identities are extremely rare. The emergence of a new identity that is inclusive of members of both traditions in the context of our own ancient conflict is perhaps a unique event. If this is indeed a new social category that is capable of resolving societal division, or even help encourage more positive community relations, then it deserves nothing less than the highest level of scepticism and rigour of methods that social science provides.

Myth 1: Northern Irish identification is increasing

There is little evidence that the Northern Irish identity is increasing in popularity in any substantial way. In surveys carried out between 2001 and 2008 there was a large rise in the proportion of young Protestants choosing to identify as Northern Irish, however this trend has now largely ended. Significantly, the establishment of the Assembly and power-sharing executive have had no discernible impact on preference for a cross-community identity.

Similarly, the Northern Irish identity appears to have had little impact on the institutions. The Hansard record of plenary debates in the Assembly shows that MLAs have only used the phrase ‘Northern Irish’ 154 times between 1998 and 2015. This is only a fraction of the times they have used the terms ‘British’ (6149) and ‘Irish’ (13111) and is only slightly more than uses of the word ‘French’ (149).

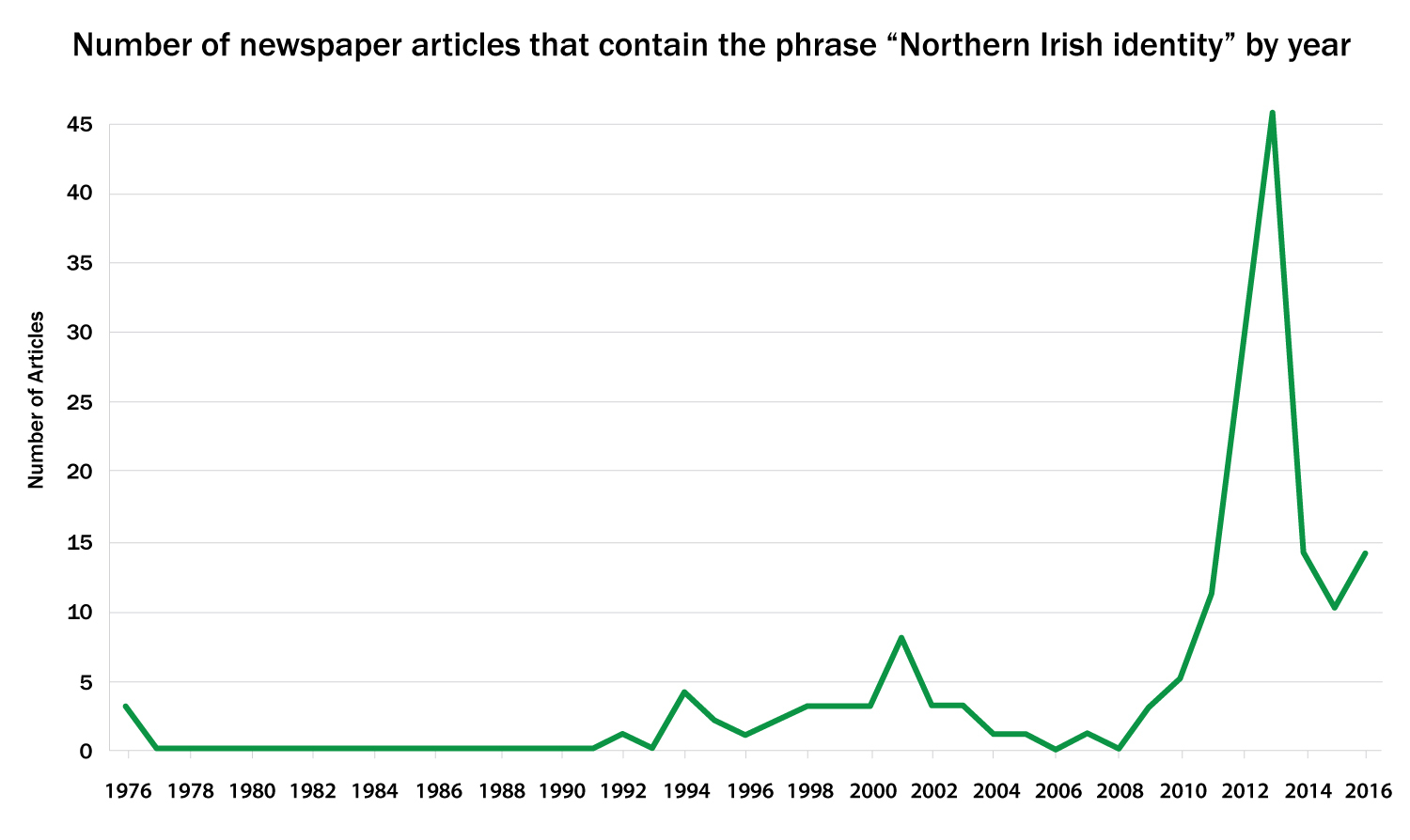

There is however evidence that there is a lot more reporting on this identity in the media, particularly since the 2011 census (see Figure 2). This may be one factor explaining the perception that the Northern Irish identity is becoming more common.

Figure 2: Showing the number of newspaper articles that contain the phrase “Northern Irish identity” by year (Nexis, 2016).

For further work in this area with a similar analysis of newspaper data please see Fenton, 2015 here.

Myth 2: The Northern Irish are a part of the cosmopolitan middle class

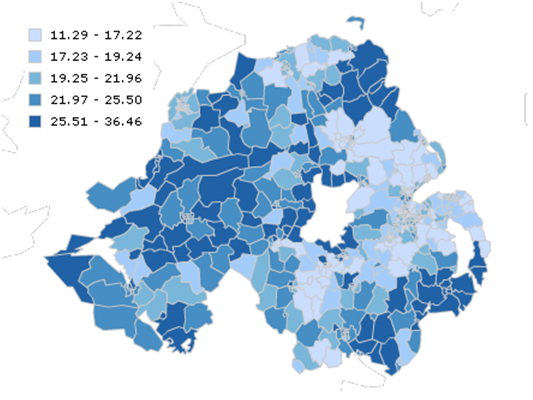

The prevailing stereotype suggests that Northern Irish identifiers are primarily middle class and tend to live in and around more cosmopolitan areas. Countering this narrative, Figure 3 shows data from the 2011 census that indicates that Northern Irish identifiers are well dispersed around the region. Although there is a higher concentration of Northern Irish identifiers in urban areas, the difference only amounts to about 5%. Previous studies have indicated that those who identify this way tend to live further from areas that have experienced higher levels of conflict related violence (Lowe & Muldoon, 2010).

Figure 3: Showing the population density of Northern Irish identifiers. The key indicates the percentage of people in that area with a Northern Irish identity. (Statistics NI, 2012).

Also, counterintuitively, income seems to play no significant role in predicting identity choices. The true picture is then a good deal more complex that the prevailing wisdom suggests.

Myth 3: Northern Irish identifiers share a preference for moderate politics

Northern Irish identifiers are more likely to vote for the centre ground parties such as the Alliance than their Irish and British counterparts, and they are also more likely to consider themselves to be neither unionist nor nationalist. The difference is statistically significant but very small.

For example, while 4.2% of those identifying as Irish or British say they are most likely to vote Alliance in the previous general election, the figure is a mere 11.6% for Northern Irish respondents. Similarly, there is little increased support for the Greens (1.8% compared with 4.6%) or NI21 (0.2% compared with 0.7%) (Ipsos, 2016).

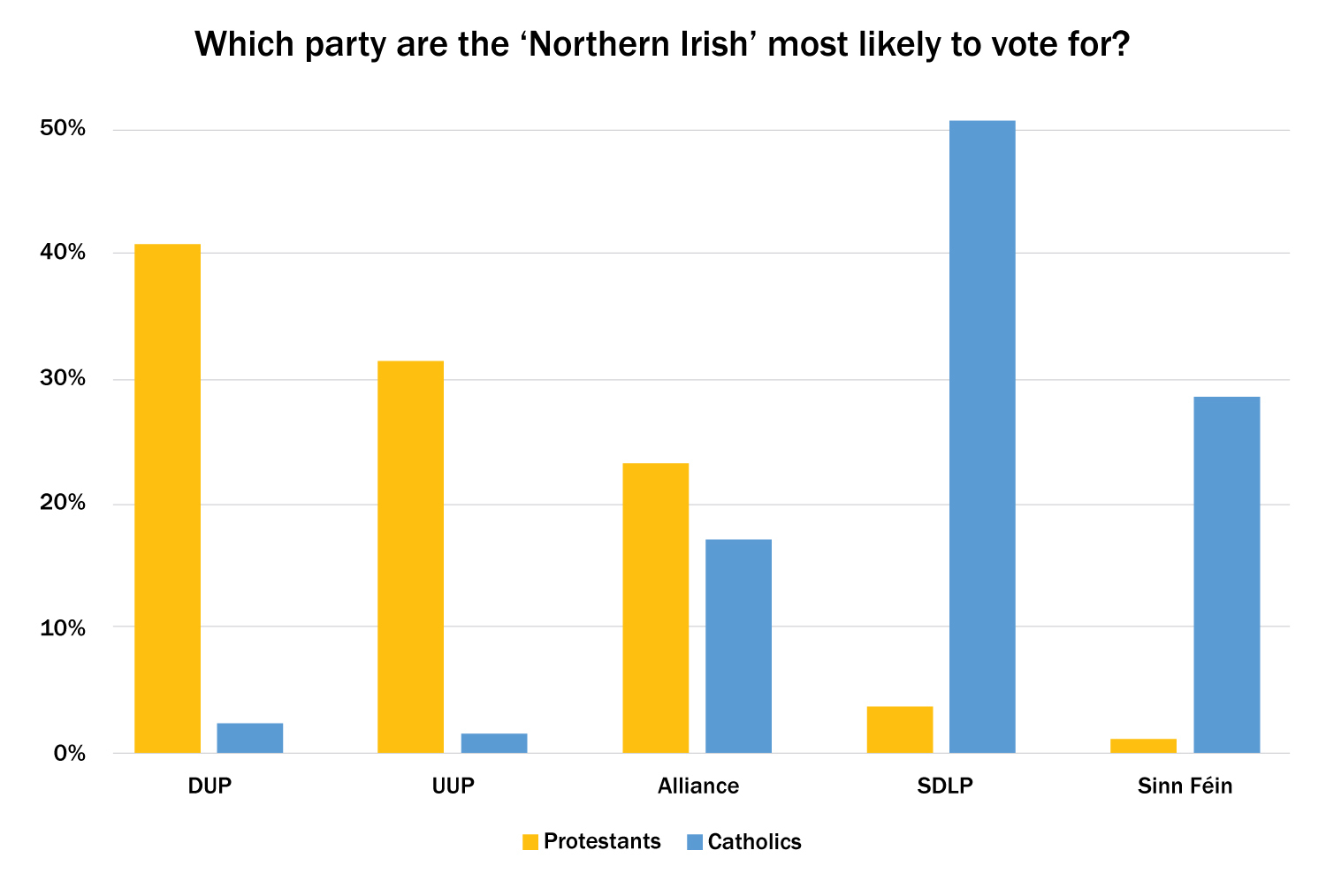

Figure 4 shows the party preferences of people who identify themselves as Northern Irish. It is clear that the vast majority of both Catholics and Protestants who identify this way still prefer to vote for nationalist and unionist parties, and almost no one crosses the aisle into the other camp.

The latest Life and Times survey (ARK, 2015) also shows that Northern Irish identifiers are still more likely to consider themselves nationalist and unionist than neither. It is religion, not national identity that is the primary determinant of party preference.

Image titleFigure 4: Showing the party preferences among Catholic and Protestant Northern Irish identifiers only (Ipsos, 2015).

So what does the Northern Irish identity mean?

Now that the common narratives have been tested to destruction what can we say about this new identity? The academic literature in this area using qualitative methods is keen to emphasise that even those who identify this way are not entirely certain of its meaning. This ambiguity of meaning is even said to be one of the appeals of Northern Irishness (Waddell & Cairns, 1991, Moxon-Browne, 1991).

There is also a constructive grammatical ambiguity about the difference between northern Irish (with a small ‘n’) and Northern Irish. Someone can claim northern Irishness while still being entirely Irish, but emphasising that they are from the north. Similarly, someone who feels entirely British can claim this as a UK regional identity in the same way as someone from England, Scotland or Wales.

Studies have also shown that often people claim a Northern Irish identity somewhat disingenuously as a kind of ‘safe label’ they can use in a potentially conflictual intergroup interaction (Todd et al., 2006).

There is however some scope for this to be what social psychologists call, a common ingroup identity. That is a new identity, truly inclusive of different social categories and related to a reduction in prejudicial attitudes.

This could give hope to those who strongly support encouraging the emergence of Northern Irishness in the region.

However, it should be acknowledged that most people do not feel Northern Irish, and there is a good deal of hostility towards normative claims that the only way to reduce tensions is to insist that others abandon their affinity with their home nation.

There are those too who would insist that the Irish and British identities are sufficient to act as a common ingroup, and both are just as inclusive and multicultural as Northern Irish.

Whatever the validity of any of these claims, and in spite of having no clear unique culture, flag, passport, anthem, language, shared history, currency, traditions of state, or any of the other usual trappings of national belonging, the Northern Irish identity is not going away anytime soon, and political representatives could do well to move to acknowledge this new and highly unlikely constituency.

- Kevin McNicholl is a post-doctoral research assistant at Queen's University Belfast who has researched the Northern Irish identity.

- RETURN to the main article here.

Some of the data used in this piece comes from a new and extremely large dataset from Ipsos Mori. The dataset includes over 11,000 cases collected between 2015-2016 and is freely available by contacting the author at [email protected]. Click here to read a full list of reference for this article.

This project has received support from the Northern Ireland Community Relations Council which aims to promote a pluralist society characterised by equity, respect for diversity, and recognition of interdependence. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the council.